Regurgitation of recently consumed material in canines, where the expelled contents retain their original form and have not undergone significant breakdown, often indicates an issue within the esophagus or stomach. This event typically occurs shortly after eating and is characterized by the effortless expulsion of the material, lacking the forceful abdominal contractions associated with vomiting. The consistency of the ejected matter, closely resembling the ingested food, is a key identifying factor.

Identifying the underlying cause is paramount for the animal’s well-being. It provides critical insights into potential problems such as esophageal obstruction, rapid eating, or gastrointestinal sensitivities. Early intervention, guided by a thorough veterinary assessment, can prevent further complications and improve the animal’s quality of life. Historical cases show that delayed diagnosis of such issues can lead to malnutrition and dehydration.

A comprehensive investigation, potentially including diagnostic imaging and dietary modifications, is typically recommended to determine the etiology. The following sections will delve into the common causes, diagnostic procedures, and available treatment options for this condition, providing a structured approach to managing such cases effectively.

Management Strategies

Effective management hinges on identifying the root cause. Observation and prompt veterinary intervention are crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Tip 1: Observe Eating Habits: Closely monitor the dog’s eating behavior. Rapid consumption or gulping can contribute to the issue. Use slow-feeder bowls to regulate intake speed.

Tip 2: Dietary Modification: Consult a veterinarian regarding appropriate dietary changes. Smaller, more frequent meals may ease the digestive process. Avoid highly processed foods.

Tip 3: Rule Out Food Sensitivities: Conduct a food elimination trial, under veterinary supervision, to identify potential allergens or intolerances that may be contributing to the problem.

Tip 4: Monitor Water Intake: Ensure constant access to fresh water, but regulate intake if excessive drinking immediately before or after meals is suspected to be a contributing factor.

Tip 5: Veterinary Examination: Seek immediate veterinary care if the event is persistent or accompanied by other signs, such as lethargy, diarrhea, or weight loss. Diagnostic tests may be necessary.

Tip 6: Esophageal Assessment: If esophageal dysfunction is suspected, specialized diagnostic imaging, such as fluoroscopy, may be required to assess esophageal motility and identify potential obstructions.

Tip 7: Medication Considerations: If an underlying medical condition is diagnosed, adhere strictly to the prescribed medication regimen and dosage as directed by the veterinarian.

Adherence to these strategies can contribute to mitigating the issue and supporting digestive health. Consistent monitoring and timely intervention are vital for the animal’s well-being.

The subsequent section will summarize key findings and emphasize the importance of ongoing veterinary care in maintaining canine gastrointestinal health.

1. Rapid ingestion

Rapid ingestion, characterized by swift consumption without adequate mastication, is a significant contributing factor to the regurgitation of undigested food in canines. This behavior bypasses the initial stages of digestion, placing an increased burden on the stomach and potentially leading to the expulsion of relatively unprocessed food.

- Insufficient Mastication

When food is swallowed quickly, the mechanical breakdown initiated by chewing is minimized. Large particles of food enter the stomach, hindering enzymatic digestion. This can overload the stomach’s capacity to process the bolus efficiently, increasing the likelihood of regurgitation. For instance, a dog that rapidly consumes dry kibble without sufficiently moistening it with saliva may be more prone to this issue.

- Increased Air Swallowing (Aerophagia)

Rapid eating often leads to increased air intake, a phenomenon known as aerophagia. The presence of excessive air in the stomach can distend the organ, triggering the regurgitation reflex. This is particularly common in brachycephalic breeds (e.g., Bulldogs, Pugs) due to their anatomical predisposition to swallowing air while eating. The air displacement can force the undigested food back up the esophagus.

- Overwhelming Gastric Capacity

Consuming a large volume of food quickly can overwhelm the stomach’s capacity, stretching its walls and stimulating the vomiting center in the brain. The stomach is unable to effectively churn and mix the food with gastric juices, resulting in the expulsion of undigested material. This is especially relevant for dogs fed one large meal per day, as opposed to multiple smaller meals.

- Esophageal Distension and Reflex

The bolus of food is so large and difficult to swallow that the esophagus starts to stretch, creating a reflux that push food upward.

The multifaceted consequences of rapid ingestion highlight its direct link to the regurgitation of undigested food in canines. Implementing strategies to slow down the eating process, such as using slow-feeder bowls or providing smaller, more frequent meals, can mitigate these effects and improve digestive health. These interventions address the underlying mechanism by promoting thorough mastication, reducing air swallowing, and preventing gastric overload, ultimately decreasing the frequency of regurgitation events.

2. Esophageal issues

Esophageal issues represent a primary cause of undigested food regurgitation in canines. The esophagus, a muscular tube connecting the mouth to the stomach, facilitates the passage of food. Dysfunction or structural abnormalities within this organ can impede normal transit, leading to the expulsion of food before digestion commences. Conditions like megaesophagus, characterized by esophageal dilation and reduced motility, impair the effective movement of food to the stomach. Consequently, undigested food accumulates within the dilated esophagus and is subsequently regurgitated. Strictures, or narrowing of the esophageal lumen, can also obstruct the passage of food, causing similar regurgitation. Foreign bodies lodged in the esophagus similarly create a physical barrier, preventing food from reaching the stomach and resulting in regurgitation.

The nature of esophageal issues dictates the presentation and management. For instance, cases of megaesophagus require modified feeding strategies, such as elevated feeding and frequent, small meals, to utilize gravity and bypass the esophageal dysfunction. Strictures may necessitate surgical intervention or balloon dilation to restore esophageal patency. In instances of foreign body obstruction, prompt endoscopic or surgical removal is essential to prevent further esophageal damage and resolve the regurgitation. Furthermore, esophagitis, or inflammation of the esophageal lining, can disrupt normal esophageal function, contributing to regurgitation. This inflammation may arise from acid reflux, trauma, or infection, requiring medical management to alleviate symptoms and promote healing.

In summary, esophageal issues are a critical determinant in cases of undigested food regurgitation in canines. Accurate diagnosis, involving radiographic or endoscopic evaluation, is vital for identifying the specific underlying esophageal abnormality. Effective management, tailored to the specific condition, aims to restore normal esophageal function, prevent complications such as aspiration pneumonia, and improve the animal’s quality of life by minimizing regurgitation episodes. The understanding of these issues and implementation of appropriate strategies is paramount for canine health management.

3. Food intolerance

Food intolerance represents a significant etiological factor in instances of canine regurgitation of undigested food. Unlike food allergies, which involve an immune system response, intolerances result from the digestive system’s inability to properly process specific food components. This impaired digestion leads to gastrointestinal upset and, consequently, the expulsion of undigested food matter. The temporal proximity of food consumption and the regurgitation event, coupled with the presence of recognizable food particles, strongly suggests a potential intolerance.

The pathogenesis of food intolerance-related regurgitation arises from several mechanisms. Deficiencies in specific digestive enzymes may prevent complete breakdown of complex carbohydrates or proteins, leading to irritation of the gastric or esophageal mucosa. For example, a dog lacking sufficient lactase enzyme may experience regurgitation after consuming dairy products. Similarly, sensitivities to additives, preservatives, or artificial colorings present in commercial pet foods can induce inflammatory responses in the gastrointestinal tract, triggering regurgitation. Furthermore, dietary imbalances or excessive consumption of certain nutrients, such as fats, may overwhelm the digestive capacity, resulting in incomplete digestion and subsequent regurgitation.

Addressing food intolerance-related regurgitation requires a systematic approach. Identification of the offending food component is crucial, often achieved through a controlled elimination diet trial conducted under veterinary supervision. This involves feeding a novel protein and carbohydrate source for a defined period and gradually reintroducing individual ingredients to monitor for adverse reactions. Dietary management, emphasizing hypoallergenic or limited-ingredient diets, forms the cornerstone of treatment. The elimination of poorly tolerated food items reduces digestive stress and alleviates the regurgitation. In conclusion, food intolerance is a notable contributor to canine regurgitation of undigested food, necessitating careful dietary evaluation and tailored nutritional strategies for effective management.

4. Gastric motility

Gastric motility, the coordinated contractions of the stomach muscles responsible for mixing and propelling food through the digestive tract, is intrinsically linked to instances of regurgitation of undigested food in canines. Disruption of normal motility patterns can significantly impede the digestive process, leading to the premature expulsion of stomach contents.

- Delayed Gastric Emptying (Gastroparesis)

Gastroparesis, characterized by a slowing or cessation of gastric emptying, represents a primary motility disorder. When the stomach fails to effectively transfer food to the small intestine, undigested material accumulates, increasing the risk of regurgitation. This may stem from nerve damage, metabolic disorders, or certain medications. In dogs, gastroparesis can manifest as postprandial regurgitation, where undigested food is expelled hours after consumption.

- Gastric Dysrhythmias

Gastric dysrhythmias involve abnormal patterns of gastric contractions, disrupting the orderly mixing and propulsion of food. These irregularities can hinder efficient digestion, resulting in the regurgitation of undigested or partially digested food. Examples include tachygastria (increased gastric contractions) and bradygastria (decreased gastric contractions), both of which can disrupt normal gastric emptying.

- Gastric Obstruction

While technically a mechanical issue, gastric obstruction significantly impacts motility. A physical blockage, such as a foreign body or tumor, impedes the normal flow of food through the stomach. The resulting backup of undigested material often leads to regurgitation. The severity and frequency of regurgitation depend on the degree and location of the obstruction.

- Effect of Diet

Diet composition has a relationship with how Gastric work. A diet rich in fat can sometimes slow the gastric, causing problem.

The interplay between gastric motility and the regurgitation of undigested food underscores the importance of assessing gastric function in affected canines. Diagnostic procedures, such as gastric emptying studies, can help identify motility disorders. Management strategies, including dietary modifications, prokinetic medications, and surgical intervention (in cases of obstruction), aim to restore normal gastric motility and alleviate regurgitation episodes.

5. Diet composition

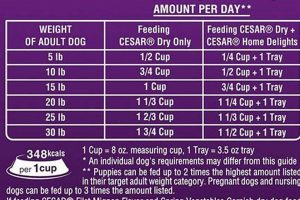

The composition of a canine’s diet directly influences the occurrence of undigested food regurgitation. The ratio of protein, carbohydrates, and fats, along with the inclusion of fiber, preservatives, and artificial additives, affects gastric emptying, digestive enzyme activity, and overall gastrointestinal health. Imbalances or sensitivities to specific dietary components can disrupt the normal digestive process, leading to the expulsion of food before adequate breakdown. For instance, diets high in indigestible fiber can overwhelm the stomach, while excessive fat content can delay gastric emptying, both predisposing to regurgitation. A diet lacking essential nutrients may impair enzyme production, resulting in incomplete digestion.

Consider a scenario where a dog is transitioned rapidly from a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet to one that is predominantly fat-based. The sudden increase in fat intake may exceed the digestive capacity of the pancreas, leading to incomplete fat digestion and subsequent regurgitation. Similarly, diets containing high levels of artificial additives or preservatives can trigger inflammatory responses in the gastrointestinal tract of sensitive individuals, disrupting motility and causing regurgitation. Furthermore, large particle sizes in dry kibble, if not adequately chewed, can contribute to gastric overload and regurgitation.

Understanding the connection between diet composition and regurgitation of undigested food highlights the necessity of carefully selecting canine diets. Considerations include nutrient balance, ingredient quality, and the presence of potential allergens or irritants. Slow and deliberate dietary transitions are crucial to allow the digestive system to adapt. In cases of recurrent regurgitation, a veterinary-guided elimination diet trial can help identify specific dietary triggers. Ultimately, a well-formulated, digestible diet, tailored to the individual dog’s needs, plays a pivotal role in minimizing regurgitation and promoting gastrointestinal health.

6. Veterinary assessment

The regurgitation of undigested food in canines necessitates a thorough veterinary assessment to identify the underlying etiology and implement appropriate management strategies. The presence of undigested food in the regurgitated material suggests a dysfunction in the early stages of digestion, prompting a comprehensive evaluation of the esophagus, stomach, and proximal small intestine. The initial assessment typically involves a detailed history, encompassing dietary habits, eating behavior, frequency and timing of regurgitation episodes, and any concurrent clinical signs, such as weight loss, lethargy, or abdominal discomfort. Physical examination aids in detecting palpable abnormalities, assessing hydration status, and evaluating overall body condition.

Diagnostic investigations are critical for pinpointing the cause. Radiographic imaging, including contrast studies, can reveal esophageal abnormalities like megaesophagus or strictures, as well as gastric foreign bodies or masses. Endoscopic examination allows direct visualization of the esophagus and stomach, facilitating biopsy collection for histopathological analysis. Gastric emptying studies assess the rate at which food exits the stomach, identifying motility disorders like gastroparesis. Blood work, including complete blood count and serum biochemistry, helps rule out systemic diseases that can contribute to regurgitation. For instance, hypothyroidism can slow gastric motility, while liver or kidney disease can indirectly affect digestive function. In cases of suspected food intolerance, a controlled elimination diet trial, guided by a veterinarian, is essential for identifying offending dietary components. The results of these investigations inform the development of a tailored treatment plan.

In conclusion, the veterinary assessment is paramount in cases of canine regurgitation of undigested food. The diagnostic process enables the differentiation between various potential causes, ranging from esophageal abnormalities to gastric motility disorders and food intolerances. Accurate diagnosis informs targeted treatment, which may involve dietary modifications, medication, surgery, or a combination thereof. The ultimate goal is to restore normal digestive function, alleviate regurgitation episodes, and improve the animal’s overall well-being. Delaying or forgoing veterinary assessment can lead to prolonged discomfort, malnutrition, and potentially life-threatening complications like aspiration pneumonia.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following addresses common queries regarding the regurgitation of undigested food in canines, providing informative answers based on veterinary knowledge and best practices.

Question 1: Is regurgitation of undigested food the same as vomiting?

No, regurgitation and vomiting are distinct processes. Regurgitation is the passive expulsion of undigested food from the esophagus or stomach, typically occurring shortly after eating and lacking forceful abdominal contractions. Vomiting, in contrast, involves forceful expulsion of stomach contents, often partially or fully digested, accompanied by retching and abdominal contractions.

Question 2: What are the potential causes of a dog regurgitating undigested food?

Numerous factors can contribute, including rapid eating, esophageal abnormalities (e.g., megaesophagus), food intolerances, gastric motility disorders (e.g., gastroparesis), and dietary composition imbalances. A thorough veterinary examination is necessary to determine the specific underlying cause.

Question 3: When should veterinary attention be sought for a dog regurgitating undigested food?

Veterinary attention is warranted if the regurgitation is frequent, persistent, or accompanied by other clinical signs such as weight loss, lethargy, loss of appetite, diarrhea, or difficulty breathing. Prompt veterinary care is also advised if there is any suspicion of foreign body ingestion.

Question 4: How is the cause of regurgitation diagnosed?

Diagnosis typically involves a combination of physical examination, detailed history, blood tests, radiographic imaging (e.g., X-rays, barium swallow), and potentially endoscopic examination. Gastric emptying studies may be performed to assess gastric motility. Elimination diet trials are useful for identifying food intolerances.

Question 5: What dietary changes can help manage regurgitation?

Dietary modifications often include feeding smaller, more frequent meals, using slow-feeder bowls to prevent rapid eating, and providing a highly digestible diet. In cases of food intolerance, a hypoallergenic or limited-ingredient diet may be recommended. The specific dietary adjustments should be guided by veterinary advice.

Question 6: Is regurgitation of undigested food always a serious problem?

While occasional regurgitation may not be cause for alarm, persistent or frequent episodes warrant veterinary investigation. Chronic regurgitation can lead to malnutrition, dehydration, and aspiration pneumonia. Early diagnosis and appropriate management are essential to prevent complications and maintain canine health.

The information presented provides a general overview. Individual cases may vary, and veterinary consultation is crucial for accurate diagnosis and tailored treatment.

The following section will provide resources for further information and support regarding canine digestive health.

Conclusion

The preceding sections have outlined the various facets associated with canine regurgitation of undigested food. A wide spectrum of potential etiologies, from dietary factors to esophageal abnormalities and motility disorders, necessitates a meticulous diagnostic approach. Early recognition of this symptom is paramount for initiating appropriate interventions, thereby mitigating potential long-term health consequences.

Sustained awareness and proactive veterinary care are essential for maintaining canine gastrointestinal well-being. Continued research and advances in diagnostic and therapeutic modalities promise to further improve the management of this complex condition. The health and comfort of the animal are the primary concern; therefore, vigilance and informed decision-making are crucial.