Regurgitation in canines, characterized by the expulsion of food shortly after consumption, is a relatively passive process often mistaken for vomiting. The expelled material is typically undigested and retains its original form, lacking the bile or partially digested appearance associated with true emesis. This event usually occurs without forceful abdominal contractions or retching.

Prompt identification of the cause is crucial, as frequent regurgitation can lead to nutritional deficiencies, esophageal irritation, and aspiration pneumonia. Distinguishing regurgitation from vomiting is vital for accurate diagnosis. Historical observations suggest certain breeds, particularly those with esophageal abnormalities, may be predisposed to this condition, highlighting the importance of recognizing breed-specific predispositions in veterinary practice.

Further discussion will explore the various potential causes of this alimentary issue, the diagnostic procedures employed to determine the underlying etiology, and the available treatment options designed to alleviate the condition and prevent recurrence. Dietary management and lifestyle adjustments will also be addressed.

Guidance Regarding Regurgitation of Undigested Aliment in Canines

These recommendations aim to provide owners with practical steps to address occurrences where a canine expels undigested food. Consistent application of these principles can aid in preventing future episodes and ensure the animal’s well-being.

Tip 1: Observe the Incident Carefully: Note the time of occurrence relative to mealtime, the appearance of the expelled matter, and the dog’s behavior before, during, and after the event. This detailed observation will assist in differential diagnosis.

Tip 2: Rule Out Rapid Consumption: Evaluate the dog’s eating habits. Rapid ingestion of food can overwhelm the esophageal capacity, leading to regurgitation. Implementing measures to slow down eating is advisable.

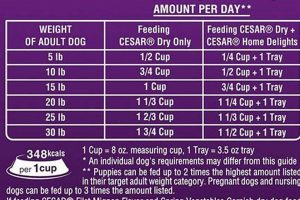

Tip 3: Consider Dietary Modifications: Experiment with smaller, more frequent meals. This reduces the bolus size, potentially minimizing the likelihood of overload. Evaluate the consistency of the food; moistened or softer textures may be easier to manage.

Tip 4: Elevate Food Bowls: Raising the food bowl can assist in utilizing gravity to facilitate esophageal transit, particularly in cases where megaesophagus is suspected or confirmed.

Tip 5: Hydration is Key: Ensure adequate hydration. Dehydration can exacerbate the problem, particularly if the regurgitated material is dry and difficult to pass.

Tip 6: Monitor for Accompanying Symptoms: Observe for signs of lethargy, coughing, or appetite loss. These indicators may suggest a more serious underlying condition requiring immediate veterinary attention.

Tip 7: De-worming protocol: Parasites can lead to vomiting or regurgitation, so make sure your dog is up-to-date on his/her de-worming treatment.

Adherence to these guidelines can contribute to minimizing instances of regurgitation and improving canine health. However, these are not a substitute for professional veterinary advice.

The subsequent sections will explore diagnostic procedures and treatment options, underscoring the importance of seeking veterinary consultation for persistent or severe cases.

1. Esophageal Motility

Esophageal motility, the coordinated muscular contractions propelling food from the pharynx to the stomach, is fundamentally linked to the regurgitation of undigested food in canines. Disruptions in this process can lead to the passive expulsion of recently ingested material, a defining characteristic of regurgitation as distinct from active vomiting.

- Megaesophagus: Impaired Peristalsis

Megaesophagus represents a significant compromise to esophageal motility, characterized by an enlarged and flaccid esophagus. This condition impairs or eliminates effective peristaltic waves, preventing the bolus of food from reaching the stomach. The undigested food accumulates within the dilated esophagus, leading to regurgitation. Congenital and acquired forms exist, each presenting unique challenges in management and prognosis. Radiographic imaging is crucial for diagnosis.

- Esophagitis: Inflammation-Induced Dysfunction

Inflammation of the esophageal lining, known as esophagitis, can directly affect esophageal motility. The inflammation can disrupt the normal muscular contractions, impairing peristalsis and causing esophageal spasms. The resulting dysmotility contributes to the retention of food within the esophagus and subsequent regurgitation. Causes of esophagitis include acid reflux, ingestion of caustic substances, and foreign body irritation.

- Neuromuscular Disorders: Interruption of Nerve Signals

Neuromuscular disorders affecting the nerves and muscles responsible for esophageal function can disrupt motility patterns. These disorders can interfere with the nerve signals that coordinate muscle contractions, leading to uncoordinated or weakened peristalsis. Affected animals may exhibit regurgitation, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), and associated signs of malnutrition. Myasthenia gravis and certain neuropathies are potential causes.

- Strictures and Obstructions: Physical Impediments

Esophageal strictures, or narrowing of the esophageal lumen, represent physical impediments to the passage of food. These strictures disrupt normal motility by obstructing the smooth progression of the food bolus. The resulting backup of undigested material proximal to the stricture often leads to regurgitation. Strictures can result from scar tissue formation secondary to esophagitis or foreign body trauma.

In summary, compromised esophageal motility, whether due to megaesophagus, inflammation, neuromuscular dysfunction, or physical obstruction, directly predisposes canines to regurgitation of undigested food. Identifying and addressing the underlying cause of the motility disorder is essential for effective management and improved patient outcomes.

2. Dietary Composition

The composition of a canine’s diet exerts a significant influence on esophageal function and the likelihood of regurgitation of undigested food. The physical characteristics, nutrient profile, and potential presence of irritants within the food can directly impact esophageal transit time and the integrity of the esophageal lining. Inappropriate dietary choices are frequently implicated as contributing factors in regurgitation episodes.

Dry kibble, if consumed rapidly and without adequate hydration, can expand within the esophagus, increasing the bolus size and potentially overwhelming esophageal motility. This is particularly problematic in breeds predisposed to esophageal abnormalities. Conversely, diets excessively high in fat can delay gastric emptying, leading to increased pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter and promoting reflux. Furthermore, certain food ingredients may elicit inflammatory responses within the esophagus, predisposing the animal to esophagitis and subsequent regurgitation. For example, commercially available foods containing high levels of artificial additives or preservatives have been anecdotally linked to increased instances of digestive upset, including regurgitation, in sensitive animals.

Therefore, careful consideration of dietary composition is paramount in managing and preventing regurgitation. Optimal diets are formulated to be easily digestible, appropriately sized for the animal, and free from potential irritants. In some cases, specialized diets with modified textures or novel protein sources may be necessary to alleviate esophageal stress and minimize the risk of regurgitation. Consulting with a veterinary nutritionist is advisable for formulating a customized dietary plan tailored to the individual dog’s needs and underlying health conditions.

3. Eating Habits

The manner in which a canine consumes its food significantly influences the likelihood of regurgitation. Aberrant eating habits can overwhelm esophageal capacity, disrupt normal digestive processes, and contribute to the expulsion of undigested food.

- Rapid Ingestion (Bolting)

Consuming food at an accelerated pace, often termed “bolting,” prevents adequate mastication and saliva incorporation. Large, poorly chewed boluses of food rapidly transit the esophagus, potentially exceeding its distensibility and triggering regurgitation. This behavior is more prevalent in competitive eating environments or among food-insecure animals.

- Greedy Eating

Greedy eating involves consuming excessive quantities of food in a single session. Overfilling the stomach increases intra-abdominal pressure, predisposing to gastroesophageal reflux and subsequent regurgitation of undigested material. This behavior may be observed in animals with underlying metabolic disorders or behavioral feeding issues.

- Insufficient Chewing

Inadequate mastication diminishes the surface area available for enzymatic digestion in the stomach. Large, unchewed food particles are more likely to be regurgitated. Dental disease, anatomical abnormalities of the oral cavity, or dietary factors (e.g., feeding exclusively soft foods) can contribute to insufficient chewing.

- Exercise After Eating

Vigorous physical activity immediately following a meal increases intra-abdominal pressure and alters gastrointestinal motility patterns. These changes can promote the regurgitation of recently consumed food, particularly if the stomach is distended.

Modifying these eating habits through behavioral training, specialized feeding bowls designed to slow consumption, and adjustments to meal frequency and portion size can significantly reduce the incidence of regurgitation. Addressing any underlying medical conditions contributing to abnormal eating behaviors is also critical.

4. Underlying Conditions

Various medical conditions can manifest as regurgitation of undigested food in canines. These conditions disrupt the normal function of the esophagus or the gastrointestinal tract, leading to the passive expulsion of recently ingested material. Identifying and addressing the underlying cause is paramount for effective management and prevention of future episodes. Congenital abnormalities, such as vascular ring anomalies constricting the esophagus, directly impede the passage of food. Acquired conditions, including megaesophagus secondary to myasthenia gravis or hypothyroidism, impair esophageal motility, resulting in food accumulation and regurgitation. Neoplastic processes affecting the esophagus or adjacent structures can also cause obstruction and regurgitation.

Furthermore, inflammatory conditions, such as esophagitis caused by acid reflux or ingestion of caustic substances, disrupt the esophageal lining and motility, predisposing the animal to regurgitation. Foreign bodies lodged within the esophagus create physical obstructions, preventing normal food passage and triggering regurgitation. Examples include bone fragments or indigestible objects. Parasitic infestations, such as Spirocerca lupi, can induce esophageal granulomas and subsequent obstruction. Systemic illnesses like Addison’s disease can indirectly affect gastrointestinal motility and contribute to regurgitation. Canine distemper virus can also cause regurgitation, especially in puppies, due to it disrupting digestive motility.

In conclusion, the regurgitation of undigested food is frequently a clinical sign indicative of an underlying medical issue. Thorough diagnostic evaluation, including radiographic imaging, endoscopic examination, and blood work, is essential to identify the primary cause. Addressing the underlying condition, whether through surgical intervention, medication, or dietary management, is crucial for resolving the regurgitation and improving the animal’s overall health and quality of life. Failure to address the root cause can lead to chronic regurgitation, malnutrition, and aspiration pneumonia.

5. Regurgitation vs. Vomiting

Differentiating between regurgitation and vomiting is critical when a canine expels food, as the underlying causes and management strategies differ significantly. Misidentification can lead to inappropriate treatment and potentially adverse outcomes. The distinction lies in the physiological processes and characteristics of the expelled material.

- Effort and Abdominal Contractions

Regurgitation is a passive process, often occurring without any noticeable abdominal contractions or retching. The expulsion of food is effortless. Vomiting, conversely, involves forceful abdominal contractions and retching as the body actively attempts to expel stomach contents. The canine may exhibit signs of nausea, such as excessive salivation and lip licking, prior to vomiting. The absence or presence of these signs is a key differentiating factor.

- Timing Relative to Meal Consumption

Regurgitation typically occurs shortly after eating, often within minutes or hours. The food has not had time to undergo significant digestion. Vomiting can occur at any time, even several hours after a meal, and may be associated with the expulsion of bile or partially digested food.

- Appearance and Composition of Expelled Material

Regurgitated material is generally undigested and retains its original form, closely resembling the food that was consumed. It may be mixed with saliva but will lack the presence of bile or partially digested stomach contents. Vomited material, on the other hand, is often partially digested, containing stomach acids and bile, which imparts a yellowish or greenish tint. The texture may be more liquid or semi-liquid compared to regurgitated material.

- Esophageal Involvement

Regurgitation often indicates a problem within the esophagus, such as megaesophagus or esophageal stricture, that prevents the normal passage of food to the stomach. Vomiting, in contrast, typically originates from the stomach or small intestine, indicating a broader range of potential gastrointestinal disorders.

The ability to accurately differentiate between regurgitation and vomiting based on these characteristics is essential for providing appropriate veterinary care. Recognizing these distinctions allows for more targeted diagnostic testing and the implementation of tailored management strategies. For example, suspecting regurgitation prompts investigation of esophageal function, while suspecting vomiting necessitates evaluation of gastric and intestinal health.

6. Aspiration Risk

Aspiration risk, the potential for inhaled material to enter the lungs, represents a significant and life-threatening complication associated with regurgitation of undigested food in canines. The passive nature of regurgitation often occurs without a coordinated swallowing reflex, increasing the likelihood of material entering the trachea rather than being directed towards the esophagus and stomach. This inhaled material can trigger a severe inflammatory response within the lungs, leading to aspiration pneumonia and potentially fatal respiratory distress. Addressing aspiration risk is, therefore, a paramount concern in managing cases involving regurgitation.

- Compromised Airway Protection

Neurological deficits, esophageal dysfunction, and altered states of consciousness can impair the normal protective mechanisms of the airway, such as the gag reflex and cough reflex. These compromised reflexes render the canine more vulnerable to aspirating regurgitated food. Animals with megaesophagus, in particular, may have a chronically dilated esophagus that can intermittently empty into the airway, especially during recumbency.

- Esophageal Volume Overload

When the esophagus is excessively distended with undigested food, as seen in cases of megaesophagus or esophageal obstruction, the sheer volume of material increases the probability of aspiration. Small amounts of regurgitated food can easily be inhaled, particularly if the animal is in a horizontal position. The increased volume overwhelms the animal’s ability to effectively clear the airway.

- Bacterial Inoculation of the Lungs

Regurgitated food often contains oral bacteria and, depending on the time elapsed since ingestion, may also contain bacteria from the upper digestive tract. Aspiration introduces these bacteria into the sterile environment of the lungs, triggering a bacterial pneumonia. The specific bacterial species present can influence the severity of the pneumonia and the choice of antibiotic therapy.

- Chemical Pneumonitis

In addition to bacterial inoculation, the acidic nature of regurgitated stomach contents, even in an undigested state, can cause chemical pneumonitis upon aspiration. The acidic pH irritates and damages the delicate lung tissue, leading to inflammation and impaired gas exchange. This chemical injury can exacerbate the inflammatory response initiated by the presence of foreign material in the lungs.

Mitigating aspiration risk in canines experiencing regurgitation requires a multifaceted approach. This includes elevating the food bowl to facilitate esophageal emptying, feeding small, frequent meals, modifying food consistency, and addressing any underlying medical conditions contributing to regurgitation. Prompt veterinary intervention is crucial if signs of aspiration pneumonia, such as coughing, labored breathing, or fever, develop. Prevention of aspiration is the primary goal; however, early recognition and aggressive treatment of aspiration pneumonia are essential for improving outcomes and minimizing morbidity and mortality associated with regurgitation.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common queries concerning the regurgitation of undigested food in canines, providing concise and informative responses based on current veterinary knowledge.

Question 1: Is regurgitation always a serious medical problem?

While occasional regurgitation might stem from dietary indiscretion or rapid eating, persistent or frequent episodes warrant veterinary assessment to rule out underlying medical conditions. Chronic regurgitation can lead to nutritional deficiencies and aspiration pneumonia.

Question 2: How can regurgitation be distinguished from vomiting?

Regurgitation is characterized by the passive expulsion of undigested food, often shortly after eating, without abdominal contractions or retching. Vomiting involves forceful expulsion, preceded by nausea, and the vomitus typically contains digested food or bile.

Question 3: What dietary modifications can help minimize regurgitation?

Smaller, more frequent meals, elevated food bowls, and moistened food may aid in reducing regurgitation episodes. A veterinary nutritionist can provide tailored dietary recommendations based on the canine’s individual needs and underlying medical conditions.

Question 4: Which diagnostic tests are typically performed to determine the cause of regurgitation?

Diagnostic procedures may include radiographic imaging (X-rays), endoscopic examination of the esophagus, blood work to assess organ function and rule out systemic diseases, and potentially, advanced motility studies to evaluate esophageal function.

Question 5: Can certain breeds be predisposed to regurgitation?

Yes, certain breeds, particularly those with conformation predispositions to esophageal abnormalities, such as brachycephalic breeds and breeds prone to megaesophagus, may be at increased risk of regurgitation.

Question 6: What are the potential long-term consequences of untreated regurgitation?

Untreated regurgitation can result in malnutrition, weight loss, esophageal irritation, and the development of aspiration pneumonia, a potentially life-threatening respiratory infection.

In summary, while dietary and management modifications may alleviate some cases of regurgitation, veterinary intervention is often necessary to diagnose and address the underlying cause. Early detection and appropriate treatment are crucial for preventing complications and improving the canine’s overall health.

The following section will delve into specific treatment options for addressing canine regurgitation.

Concluding Remarks

The preceding discussion has thoroughly examined the phenomenon of “dog throwing up undigested food,” exploring its underlying mechanisms, potential causes, diagnostic approaches, and management strategies. A key takeaway remains the critical need to differentiate regurgitation from vomiting, as this distinction directs the subsequent diagnostic and therapeutic pathways. Furthermore, recognizing and mitigating the risk of aspiration pneumonia is paramount in safeguarding the health and well-being of affected animals.

While this discourse provides valuable insights, it is imperative to acknowledge that it does not substitute for professional veterinary consultation. Canine regurgitation can stem from a multitude of etiologies, ranging from benign dietary indiscretions to serious underlying medical conditions. Therefore, prompt veterinary evaluation is essential for accurate diagnosis and the implementation of tailored treatment protocols. Continued vigilance and proactive management are crucial for minimizing the long-term consequences of this alimentary issue, thereby enhancing the quality of life for affected canines.